“The Mopla community in Andaman and Nicobar Islands,” United News of India reported on 29th April 2008, “is demanding proper recognition for their heroes, who played an indispensable role in India’s freedom movement.” [1] As I surveyed the newspapers for a ‘history problem’ of contemporary interest, which could be used to illustrate the interplay between argument, narrative, evidence and perspective, this report caught my eye – Here was a community which had adopted a certain perspective regarding the role of its ancestors in the Indian freedom movement and was now seeking to influence the perspective of the larger society on the issue. It was obvious that if they were to have a chance of influencing the perspective of others, they would have to present a certain narrative – which, likely [2], would have to be supported by arguments; and those arguments, in turn, had to be based on evidences.

Further research on the topic made it apparent that the demand of the Mopla community of Andaman and Nicobar Islands was inextricably tied to the long – and complex – history of the Mopla community on the mainland (specifically, the Malabar region of present-day Kerala). Members of the community had a long history of participation in revolts, and the 1971 decision of the Kerala government to grant the active, largely Mopla, participants of the Malabar Rebellion of 1921 [3], the status and accolade of Ayagi (freedom fighters) had led to a public controversy, and continues to be contested. [4]

In this essay, my primary objective is to highlight the interplay between perspectives, narratives, arguments and evidences as I explore the issue of ‘the status of Mopla rebels as freedom fighters’. In addition to this, my secondary objective would be to showcase ‘history as a process’ as opposed to ‘history as a product’. In other words, my attempt would not be to arrive at (or argue for) a conclusion, but to focus on the process of ‘creation’ of history; and to highlight that even though historical problems may often be so complex as to render any endeavour to arrive at historical ‘truths’ using one perspective nearly futile; the use of multiple perspectives and narratives that are based on sound arguments and rigorous evidences, may hold a greater possibility of bringing us closer to the truth and is hence of value.

Mopla Rebellion and Mopla Outbreaks

Before we look at the various perspectives that can be used to understand and explain the contestations around the issue of ‘Mopla rebels as freedom fighters’; in this section, let us first look at some event-based facts about the outbreaks (1836-1920) and the rebellion of 1921.

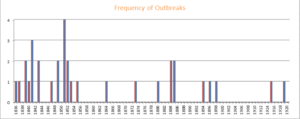

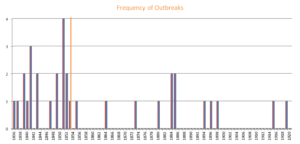

There were about 33 violent outbreaks in the then district of Malabar between 1836 and 1919 – which is approximately one outbreak every two and a half years (Dale, 1975). (Fig. 1 below shows the map of Malabar district in South India, and Fig 2 shows its frequency distribution.) Almost all the outbreaks occurred in the area between Calicut, and Ponnani, a town 35 miles to its south. 29 outbreaks comprised of attacks on local Hindu families, 3 on Englishmen residing in the district and 1 on a local Mopla family. The outbreaks were generally low-scale – other than one exceptional outbreak which occurred in Kottayam taluq in 1852 in which 17 Hindus were killed – the number of deaths in the outbreaks was confined to six. All the outbreaks were also supressed by the authorities within a few days. (Dale, 1975)

Though commonly viewed as a ‘culmination’ of this series of outbreaks, the Mopla Rebellion of 1921 was of a very different scale. It started in June-July, 1921 with Moplas in southern parts of the district congregating relatively frequently under the leadership of the local religious teachers (Hardgrave, 1977) (as was the case, for instance, on June 8th in Tirurangadi when 300-400 Moplas, some of them armed; took out a procession from the local mosque to offer prayers at the graves of those who had been killed in an earlier outbreak; and in July in a village north of Malappuram, where several thousand Moplas gathered around the mansion of a Nambudri landlord, shouting war-cries (ibid.).

The immediate trigger for the rebellion, however, seems to have been a raid by the police on August 20th in Tirurangadi which led to a clash between Moplas and the police. This clash spiralled into an open rebellion in a matter of days, and on August 22 a Mopla leader enthroned himself as king over Ernad and Walluvanad taluqs. Situation in the two districts worsened rapidly – police stations were looted and burnt, courts and government offices were ransacked, telephone and railway lines were cut and there were eyewitness accounts and newspaper reports of Hindu families – chiefly upper caste Nairs and Nambuduris – being killed by the Moplas, and temples being defiled and destroyed.

By August 30, the government of Madras informed the Government of India that “the ‘whole interior’ of South Malabar, except Palghat taluq, was in the hands of the rebels. Local civil administration had broken down; all government offices and courts had ceased to function; and ordinary business was at a standstill. In portions of the area, famine conditions were imminent. Europeans had either fled or had been evacuated, and numerous Hindu refugees of all classes had sought protection in Calicut.” (Hardgrave, 1977). A state of anarchy continued to prevail in the southern districts over the next couple of months; and the main force of the rebellion could only be crushed with the help of additional Gurkha and British troops from outside the state (as well as a newly raised local police force) around December, 1921. It was, however, only in February, 1922 that the situation was ‘normal’ enough to allow the martial law in the affected taluqs to lapse.

By then, while on the one hand, 43 Government officials had been killed and 126 wounded, and thousands of Hindu civilians had been killed, raped, forcibly converted, or driven out of their homes (the actual numbers are not agreed upon, but claims vary from a few thousand to close to a lakh); on the other hand (as per official figures), 2339 Mopla rebels had been killed, 1652 wounded, 5995 captured and over 40,000 had ‘surrendered’ (Dhanagare, 1977).

Perspectives, Arguments and Evidences

There have been a number of attempts to interpret and explain the Malabar Outbreaks and the Mapilla Rebellion – starting from the early attempts made around the mid of nineteenth century (for instance, a special commission headed in T. L. Strange was set up in 1852 to enquire into the causes of the outbreak), to the last decades of the twentieth century. Expectedly, administrators, scholars and researchers have taken various perspectives in their attempt to do so. In this section, I will begin by first listing some of the more commonly-adopted perspectives with regards to the outbreaks and the rebellion, and then describe each of these in some detail – focusing, also, on some of their main arguments, and the evidences that these arguments are based on.

One of the more commonly encountered perspectives with respect to the outbreaks is the Marxist perspective, which emphasizes the role of the material conditions of the Mopla rebels and the economic pressures that were prevalent in the region during this era. A second perspective could be broadly termed the religious perspective which stresses on the role of religious indoctrination and fanaticism in the violent outbreaks and rebellion. The third perspective could be termed an ‘anti-colonial’ perspective which highlights the role and failures of the British government as one the primary set of causes for the rebellion. And related to this, though distinct, is the final perspective which we will discuss in this essay, termed the political perspective, which underscores the substantial role played by the Khilafat movement in the Mopla rebellion of 1921.

The Marxist Perspective

Those who adopt this perspective generally interpret Mopla outbreaks as ‘peasants’ resistance and revolt’ against the land-holding classes, and argue that the rebellion was “directly and solely a response to radical challenges induced in the agricultural economy of Malabar District” (Dale, 1975; p. 85) in the 19th century.

In support of this position, they offer a number of evidences from primary and secondary sources. For instance, in a report authored by William Logan (special commissioner of the district between 1881 and 1882), they note, it was recorded that “well over 90 per cent of the big landlords in the district were Nambudris or Nairs; while majority of the Moplas held their land on lease or mortgage.” He also showed that the landed class were using the British judicial system to evict the agriculturists (the eviction decrees rose from 1891 in the year 1862 to 8,335 in 1880) and that “the courts were used more frequently against the Moplas than the Hindus” – though the percentage of Mopla agriculturists was 27% more than 33% of the eviction decrees had been issues against them.

Further, when Logan solicited petitions from Malabar agriculturists, almost three quarters of the petitioners were Moplas who were complaining against the evictions.

The Religious Perspective

Others have argued that the participants were motivated by their religious fanaticism and that “participants conducted each attack as a religious act – as a jihad, a war for Islam.” (Dale, 1975)

To substantiate their claim they point to the well documented ‘ceremonial pattern’ of the attacks (which included visit to the mosques prior to the attack, rebels divorcing their wives, dressing themselves in a religiously sanctioned manner etc.) and the invariable climax of the attacks in virtual suicides to become sahids (martyrs of the faith). Of the 350 Moplas who participated in the outbreaks, they point out, 322 died in such suicidal acts. They also note that of the 33 outbreaks at least 13 well-documented outbreaks have no obvious connection with agrarian disputes – two attacks were on British collectors (one for recovering a Hindu boy who had been forcibly converted), three attacks were on Hindu families who had apostatized from Islam, and in four cases the primary motive clearly seem to be the desire for martyrdom. And finally, they point to the strong connections between the rebels and a handful of relatively more fanatic local religious leaders.

Anti-Colonial Perspective

Those who adopt this perspective view the 1921 rebellion as a revolt against the British colonial government and their iniquitous policies, in particular; and the colonial rule in general.

They stress that till the arrival of the Portuguese, the Hindus and the Mopla community lived in relative accord and point to the primary accounts of good trade relationships between the local farmers and the Moplas who dominated the inter-coastal and overseas trade in the region. Further, Moplas were also employed in the navy and the army of the local Hindu king – indicating the trust that existed between the two communities.

War between Tipu and British had broken out in 1790 and in the most decisive battle fought by the two sides at Thirurangadi, thousands of Moplas fighting for Tipu had lost their lives. The bitter memories of the massacre of their people by the British was still afresh in their collective memory when, having taken control of the Malabar region in 1792, the British government changed the ancient land-holding arrangement in the region – strengthening the position of the land-holders and elevating them to the legal status of land-owners and reducing the agriculturist who worked the land to the legal status of mere leaseholders who were liable to be evicted from the land at the expiry of the lease. The revenue rates were also pegged quite high by the British administrators who, further, had given the revenue collection rights to the Hindu rajas and chieftains (Dhanagare, 1977). In addition to this, the British police, law courts and revenue officials too were seen as biased against the Mopla community (the eviction orders and rates, are presented as an example and evidence of this bias).

The Political Perspective

The Khilafat movement emerged out of the First World War (1914-1918) in response to the attempts of the Allied Powers to dismember Turkey (Dhanagare, 1977). There was a fear among the Muslims that the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire would mean the end of the Caliphate (the Caliph being the spiritual head of the faith) and this had led to a nation-wide political agitation (started by the Ali brothers). People who attempt to interpret the Malabar rebellion of 1921 using this perspective view the Khilafat movement and the associated political agitation in the region as the primary coalescing and driving force behind the rebellion and argue that the primary and immediate goal of the rebellion was political – which included not just the “restoration of the Caliph and his temporal powers” but also the setting up a Islamic state in the region (Moplastan).

As evidence, they point to the speeches of the local Mopla leaders such as Mampratti Thangal (a saint revered across Malabar) which contains claims such as, “In all our Muslim States there will be no expensive litigation…” Furthermore, available primary records indicate that the public meetings held in the district as a part of the movement were well attended and that the majority of the audiences at these meetings were from the Moplah community; while the participation by the Hindus was almost negligible. There are also records of public protests and processions (involving over 12,000 Moplas) and pamphlets distributed in some of these meetings to exhort the community to agitate for the Khilafat; as well as records of the arrests of Mopla leaders who were leading these protests.

A Synthesized Perspective

In the previous section, we looked at how the same set of events have been interpreted and explained differently by different set of people adopting different perspectives. The question that one is faced with, thus, is – which of these perspectives, if any, is/are correct? Or, are all of them correct? In this section, I will present a brief summary of the Mopla history, and in doing so, will attempt to present a view which synthesizes all the perspectives discussed till now.

Though conclusive evidence on the issue is hard to come by, Moplas generally trace their ancestry to 9th century Arab traders who brought Islam to South India, married local women, and settled down in the Malabar. They were known to be a mercantile community who dominated the inter-coastal and overseas trade and mostly lived in segregated settlements along the coast and in urban centres – enjoying considerable autonomy and the patronage of the king of Calicut.

After the arrival of the Portuguese – who saw the Moplas as competitors and engaged in frequent wars with them for the domination of trade and trade routes – many Moplas started moving inland looking for new economic opportunities (Hardgrave, 1977; p. 60). By the 16th century, the majority of the community (“through the interrelated processes of immigration, intermarriage and conversion” (ibid.) had become agricultural tenants. The Moplas of the interior parts were often of the lowest castes – many of whom had embraced Islam to escape the oppression of the existing caste system. Moplas in these regions were thus often very poor, of low social status and with little opportunity for education.

During the invasion of the region by Haider Ali and Tipu Sultan in the late 18th century – and their persecution of the Nairs and Nambudris – the social structure of the Malabar region was deeply shaken. On the one hand, many of these upper caste landlords had to flee the region leaving the land in the hands of the Mopla cultivators; and on the other hand, the weakened social and political position of these casts allowed the growing Mopla community (with the newfound Islamic ‘freedom’ of many of its members) to attack the upper casts much less restraint than ever before. Tipu’s defeat at the hands of the British, and the British land settlement of the 1790s which not just reinstated the Hindu landlords but also strengthened their position as the original ‘owners’ of the land severely affected the Moplas of South Malabar (who were mainly dependent on agriculture). To make matters worse – because of the strain in the relationships between the two communities caused during Haider-Tipu era, and the over-zealous use of their newfound rights by the Hindu land-owners; as well as the high rates of taxation and eviction during the first decades of the British rule – the community found itself being pressed from all sides. It was in these contexts that one must look at the Mopla outbreaks.

However, can poverty and economic exploitation alone explain the facts related to the outbreaks and the rebellion? As Dale (1975) points out, though 73% of the agriculturists were Hindus (who too suffered eviction decrees), they rarely resorted to violence and never at the scale of the Moplas. Second, even though Moplas were settled in almost all taluqs of the district, the outbreaks were centred in a small area in the southern taluqs. And finally, an increased rate of eviction did not lead to an increased incidence of outbreaks.

Dale then points to the central role played by the religious leaders such as Mambram Tangal – who acted as religious ideologues to incite/support the community to rebel against the Hindu landlords as well as to oppose the British administration. He highlights Tangal’s decree forbidding the Moplas to plough on Fridays as an example of the intertwining of the social and religious strains; and to the sudden and significant drop in the frequency of the outbreaks after the leader’s deportation from the district. Similarly, the indescribable horrors that the Hindu men, women and children – of all castes and class, and not just the landowners – were subjected to (such as flaying, chopping off limbs, raping women in front of their husbands and brothers etc.), and the planned and conscious desecration and destruction of many temples, during the Mopla rebellion, as recorded in multiple primary sources (government correspondence, court records, eyewitness accounts, newspaper reports etc.) makes it impossible to rule out the role of (at least some degree of) religious fanaticisms and indoctrination.

Similarly, the role of the British colonial government – their callousness in addressing the genuine grievances of the Moplas, the failure to understand the traditional relationships between the landlords and the agriculturists and to initiate land reforms despite repeated petitions and violence (even after the neighbouring states of Travancore and Calicut had initiated land reforms), the real/perceived biasness of their judicial system etc. too would have clearly contributed in worsening the situation.

And finally, as Dhanagare (1977) mentions, the Khilafat movement came to Malabar at a time (1920) when the tenancy issue had already become a serious cause of social discontent in the region. The linking of, and later, the merging of the tenancy issue with the broader Khilafat-Non Cooperation movement gave the tenancy movement a political form and organizational strength and momentum that it had hitherto not known.

In summary, we see that while none of the perspectives (and the related arguments and evidences) may be sufficient in themselves to interpret and explain the Mopla outbreaks between 1836 and 1920, and the Mopla rebellion of 1921; however, an attempt to synthesize the various perspectives and to carefully use the arguments and evidences put forward by them, may be a productive endeavour and help bring one closer to the truth.

Conclusion

Historical research often requires the awareness and use of narratives, perspectives, arguments and evidences. While a narrative in its most simple form can be described as ‘a description of a sequence of events’, “narrative elements exist on several layers throughout the text” [5]. These include the narrative arc, signposts and meta-narrative.

We started this essay by mentioning a contemporary news-report (establishing relevance) and highlighting its connection with the controversial and contested ‘historical issue’ of the Malabar Outbreaks and Rebellion. I then presented the ‘plan’ of the essay and my objectives behind writing it, as sign posts of the narrative to follow.

In section two, I then started by presenting some facts about the outbreaks and the rebellion – which are usually and widely agreed upon, as most of them are based on well recorded events (as opposed to opinions, conjectures etc.). This was done to demarcate a ‘common ground’. Thereafter, in section three, I listed four perspectives that different scholars have used to interpret and explain the outbreaks and the rebellion. Further, I briefly described each of the four perspectives, the arguments offered by those who adopt them, and the kind of evidences they marshal to defend these arguments. (It might be noted here that not all evidences may be equally sound and determining the soundness of different evidence too is an important part of historical research.)

In section four, I then attempted to presented a brief, synthesized narrative (using a different ‘narrative arc’ – of chronological order – for this section), and suggested that none of the four perspectives taken in isolation may be sufficient to explain the known facts about the outbreak and the rebellion; but when employed together, may provide us with a more holistic and perhaps – even more accurate – understanding of the issues involved.

Finally, using this approach I have also attempted to underscore how history is not a ‘product’ or a ‘given’ – but a process – something which is always being negotiated and in the making. However, it is as important to keep the process grounded in sound arguments and evidences – for only that can prevent us from slipping into the mire of (‘everything goes’) relativism; and may help us inch, however tentatively, towards the truth.

References

In-line References and Notes

[1] Mopla freedom heroes received no recognition. (2008, April 29). Retrieved from http://news.oneindia.in/2008/04/29/mopla-freedom-heroes-received-no-recognition-1209449013.html (Back)

[1a] Various spellings such as Mappila, Mopla, Moplah have been used in historical and contemporary texts. In this essay, I have mostly used ‘Mopla’.

[2] ‘Likely’ has been used here as cases of public opinions being changed on the basis of rhetoric (and despite the lack of sound arguments and evidences), is not unheard of. (Back)

[3] Roland Miller, The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Vol VI , Brill 1988 (Back)

[4] Panicker, M. R. (2009, January 04). Life beyond moplah. The Sunday Indian. Retrieved from http://www.thesundayindian.com/en/story/life-beyond-moplah/7/6751/ (Back)

[5] L. Stephen & Gill. J. Learning to do historical research: A primer. (Back)

Primary Sources

[1] Logan. W. (1879). A collection of treaties, engagements and other papers of importance relating to British affairs in Malabar. Calicut.

[2] Correspondence on Moplah outrages in Malabar for the years 1853-59. Vol II. Graves, Cookson & Co: Madras

[3] Nair. C. G. (1923) The Moplah Rebellion, 1921. Norman Printing Beureau: Calicut.

[4] Logan. W (1887). Malabar Manual. Vol. 1. Asian Educational Service.

Secondary Sources

[1] Hardgrave. R. L. (1977) The Mappila rebellion, 1921: Peasant revolt in Malabar. Modern Asian Studies. Vol. 11, No. 1. Pp. 57-99.

[2] Dale. S. F. (1975) The Mapilla outbreaks: Ideology and social conflict in nineteenth century Kerala. The Journal of Asian Studies. Vol. 35. No.1. pp. 85-97

[3] Dhanagare. D. N. (1977) Agrarian Conflict, Religion and Politics: The Moplah rebellions in Malabar in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries

An edited version of this article appeared in two parts in Teacher Plus magazine (January and February, 2016 issue) under the title Developing multiperspectivity: A lesson from the Mopla Rebellion.