A report based on the deliberations of the Working Group for Higher Education in the 12th Five-Year Plan (2012-17), titled Inclusive and Qualitative Expansion of Higher Education (2011), identified “access and expansion, equity and inclusion, and quality and excellence (p. 2)” as the “triple objective” for Indian higher education in the 12th FYP. Thus, institutes of higher education in India are expected to lay special emphasis on equity, plurality and demographic diversity of faculty and students; and reduce existing disparities by “attracting and facilitating the retention of students from rural and backward areas as well as differently-abled and marginalised social groups (p. 82)”.

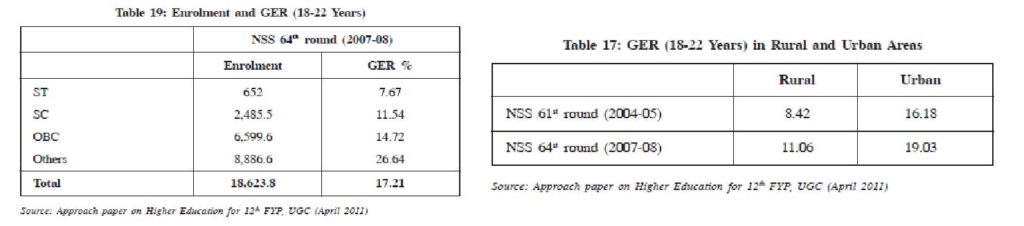

Those who have argued in favour of making ‘equity and inclusion’ two of the primary objectives of higher education point to the stark variations in the Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) of different sections of our population in higher education, even after 60-65 years of independence. For instance, according to the 64th round of NSS, as shown in the tables below, the GER for Scheduled Tribe students is close to one fourth of the ‘General’ students; and that of the Scheduled Castes students, about half of the general students. Similarly, while the GER for Urban students stood at 19% in 2007-08, the ratio for rural students was as low as 11%.

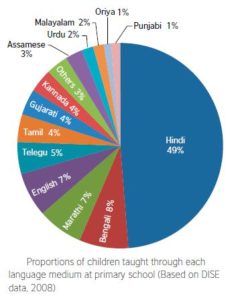

A second anomaly of the Indian higher education, which is often highlighted, is its use of English as a medium of instruction. While estimates of the number of English speakers in India have varied widely (Graddol, 2010); in 2009 the National Knowledge Commission estimated that “even now, no more than one per cent of our people use it as a second language”. Other estimates have often been in the 5-10% range. Further, it is also known that even in 2008 only about 7% of children were being taught in the ‘English medium’ at primary schools. (Refer: adjoining figure)

The above implies that every year we have hundreds of thousands of young men and women entering the portals of higher education with little or no expertise in English which is the predominant medium of instruction at this level.The English proficiency levels among the students belonging to the marginalized sections (SC/ST/OBC/minorities) are known to be even lower than the ‘general’ population [1].

And thus, it has been argued, that the two issues – low GER of the marginalized section and the use of English in Indian higher education – may in fact be intimately interlinked.

It is generally agreed that the foundations of the extant (modern) Indian education system were laid by the colonial government in the 18th and 19th centuries. Is it possible, then, that the roots of the two anomalies described above, too, lie in those early years when the blue-print of the colonial education was being negotiated among the various stakeholders [2]? What role, if any, did the social-structure of the time have to play in this?

My primary objectives in this short essay, thus, is to explore whether the educational policies and practices of the 18th and 19th century can help us better understand and explain the issues of (a) the disproportionately low participation of the marginalized section in Indian higher education, and (b) the use of English as the predominant medium of instruction in higher education in India when majority of its students, both in its schools and pre-university colleges, continue to be taught in local languages.

Structure of the Essay

European education in India during the 18th and 19th century could be divided into three broad phases. The first phase, which began in the early 18th century and ended in 1813-14, comprised almost entirely of private initiatives (with occasional government interference). The second phase, which lasted between 1814 and 1854 and saw increasing involvement of the British parliament and the East India Company in Indian education, was arguably the most important of the three phases; and, as I will attempt to show later on in the essay, many of the features that continue to characterize the Indian education system were decided in these intervening decades. The rest of the 19th century could be thought of as comprising the third phase, with the year 1882-3 marking an important milestone in this period.

Unlike some other countries which were colonised, India had a comparatively extensive and well-developed educational system, before the coming of the Europeans. And since substantial time, funds, as well as efforts, were spent by the English (and a handful of other European nationalities consisting mainly of the missionaries) in ‘responding’ to the existing education system (as opposed to creating one from the ground up); I will begin in section two, by highlighting some important features of the native education as found by the earliest English researchers.

Thereafter, in the three sections which will follow, I will sequentially present some important developments of each of the three phases that are relevant to the object of this essay. And finally, in section six, I will conclude by summarising the key points of the discussion, and highlighting some of the tentative conclusions that may be drawn about the influence of the 18 and 19th century educational practices and policies on the two issues of the higher Indian education discussed above.

- Native Education

In 1835, Mr W. Adam was appointed by Lord Bentinck to investigate the state of education in Bengal (and Bihar) province. He produced three detailed reports over the next three years which provide an authentic account of the native education in these regions during the period.

Adam reported that there were four types of native schools (a) Hindu elementary schools or Pathsalas (b) Hindu schools of (higher) learning or Tols (c) Muslim elementary schools, and (d) Muslim schools of learning or Muktabs

2.1 Elementary Education

The Hindu elementary schools existed in most villages and the teachers were ‘village officers’ “supported not by regular fees, but by presents…varying in monthly value from one-quarter of a rupee to five rupees.” (Thomas, 1891; p. 6). Of the 639 teachers surveyed in one of the districts, the vast majority (about 82%) of the teachers belonged to three upper-caste people: 369 from Kayastha, 107 Brahmin, 50 Sadgop (Acharya, 1979; 1984). Adam however notes that though the teachers belonged mainly to the Kayasth, or writer caste, they were “little respected and poorly rewarded” and “nor was there any inducement to persons of talent or character to take-up the profession.”

As far as the students of these elementary schools were concerned, the situation was only slightly better. In the district of Burdwan, for instance out of the 13,190 students, almost half were from the same three uppermost castes – Brahmin 3,429, Kayastha 1846, Sadgop 1254. About 5% belonged to 16 lowest castes and the rest represented a mix of castes and religions. Moreover, the teaching was completely oral and books or even manuscripts were ‘entirely unknown’. The education, was thus, almost entirely dependent on the skills, inclination and the ‘favours’ of the lone teacher (for there were rarely more than one teacher in a village).

The following remark by Thomas (1891, p. 7), though not precise, may be broadly relevant here: “It must not be imagined that these schools were intended for the lowest or even the lower classes. Theoretically open to all but low castes or outcasts, they were resorted to chiefly by the sons of the shop-keeping, trading, merchant, and banking castes.”

The Muslim elementary education was carried out mainly by ‘private tutors’ who was associated with a Muslim family but was allowed to take other students. The medium of instruction was Persian (which was also the language of the courts of law till 1835), and surprisingly, almost half the students in these schools were Hindus – primarily Brahmins or those belonging to the Kayastha caste (Thomas, 1891; p. 12).

2.2 ‘Higher’ Education

Unlike the pathsalas or elementary schools the Tols or Hindu schools of higher learning were generally held in high repute in the community; but they were completely monopolized by the Brahmins: “Although theoretically the study of grammar, lexicology, poetical and dramatic literature, rhetoric, and astronomy were open to be studied by inferior castes, and only law, philosophy, mythology were the exclusive inheritance of the Brahmans, yet, except in the case of medicine, which was confined to the, Vaidyas or medical caste, all higher education was imparted only by Brahman teachers and received only by Brahman boys. (ibid; p. 8)”

Moreover, the teaching conducted in the pathsalas were so disconnected with the education in the Tols, that the pre-requisite knowledge had to be obtained by the (mostly Brahmin) students not in the pathsalas but at their home. The proportion of Tols to elementary schools was about 1:3 and only about one-tenth of the students in elementary schools studied in the Tols.

The general picture that emerges, thus, is that while the teaching in Hindu elementary education was still dominated by the upper castes, it had passed on from the hands of the Brahmins or priestly class to those of the Kayastha. Moreover, it was mostly designed to meet the needs of the trading and banking communities and perhaps some of the (bigger) agriculturists. And though students from all castes were being taught in these schools (which, Acharya suggests, may have been on account of the Kayastha teachers’ willingness to take students from other communities, and thus improve their income), the student-body consisted of a disproportionate (almost 50%) number of students from the three upper castes. Surprisingly, the three castes put together, also formed the major chunk of the student body in the Persian (elementary) schools.

The Hindu ‘higher’ education, on the other hand, which was on the lines of a liberal education (and included studies in grammar, logic, rhetoric, mathematics, and metaphysics), was under the absolute dominance of the Brahmins. Teaching and learning at the elementary level had almost no connection with the education imparted in the Tols – and thus any student seeking admission in the Tols was completely dependent on the favours of Brahmin teachers, who continued to use their hold on higher education to keep up their elevated position in the society.

- Phase One: 18th Century to 1813

3.1 Vernacular for the Masses; English for the Classes

The first phase of the European education chiefly consisted of missionary led activities in various parts of the country. Some of the important issues which emerged in this phase were (a) the place of religious (which was equated to Christian) education in the education of ‘natives’ (b) the provision of teachers and the language to be employed as the medium of instruction, and (c) production of vernacular literature (mainly, translations of the Bible).

Despite consistent and notable efforts, the missionaries continued to face significant difficulties; and with limited support from the British government – at the turn of the 18th century it was estimated that less than 1000 students were receiving instructions in European schools (Thomas, 1891). This changed in the early decades of the 19th century but the number of students instructed in their schools, as a proportion of the total students, continued to remain low. Moreover, most students in the missionary schools were usually orphans or those from the lower castes; and the focus was on vernacular education as opposed to education in English.

However, even in this early phase, the few attempts that were made to provide English education seem to have been for the benefit of students from higher classes. For example, as Thomas (1891) notes, “The first project for native education which can in any way be ascribed to the Government was that of Mr Sullivan, resident at Tanjore, who in 1784 propounded a scheme for setting up English schools for the higher classes of every province.” These schools were started, and later taken over by The Company and Thomas reports that, “The pupils mainly Brahmans, made no objection to a little Christianity through the medium of the English language and those in authority went so far as to contribute to the maintenance of the schools.”

Another example from approximately the first phase – though from three decades later – was the setting up of ‘Hindu College’ at Calcutta. At the initiative of David Hare, in 1816, a number of the prominent Hindus of the city met to found a college for teaching European knowledge – The college, however, was to be reserved for Hindus of ‘good social status’. An initial amount of £11,318 sterling was raised through private contributions which helped in managing it – precariously – through the early years. In 1819 it was endowed by the government with a grant of sterling 25,000 a year; the students, however, continued to come primarily from the upper classes.

3.2 Tilt towards Orientalism

Another important feature of this phase was the beginning of an ‘oriental tilt’ among the administrators who were in the position to influence Indian education: “In 1784 Warren Hastings, then Governor -General, with the double object of arresting the decay of oriental learning and of encouraging cordial feeling between the English and their subjects, determined on the establishment, of an Arabic College or Madrassa at Calcutta. The promotion of Orientalism was thenceforth until the year of Macaulay’s famous minute, 1835, the settled policy of the Government.” (ibid)

The College at Calcutta was followed by the establishment of the Sanskrit College at Benares with the supposed purpose of “providing expounders of the Hindu law” and the internal discipline of the college was based on the second and third chapter of the ‘Institutes of Manu’.

Thus, we see that the first phase of European involvement was limited, but characterised by, the efforts of the missionaries to impart primarily elementary education in vernacular languages to the lower classes; occasional efforts to set up English schools for the higher classes, and a tilt (in the Company’s administration) towards support for Oriental (i.e. Sanskrit and Arabic) learning.

- Phase Two: 1814 to 1854

All through the first phase, The East India Company had successfully resisted taking on any formal obligation for the education of the local population in India – especially an attempt to force an introduction of an education clause when the charter had come up for renewal in 1793. However, in 1813 the following regulation was included in the Charter: “That a sum of not less than one lakh of rupees in each year shall be set apart and applied to the founding and maintaining of colleges, schools, public lectures, and other institutions for the revival and improvement of literature, and encouragement of the learned natives of India, and for the introduction and promotion of a knowledge of the sciences among the inhabitants of the British territories in India.” (as quoted in Thomas, 1891)

4.1 Support for Oriental (Sanskrit, Persian and Arabic) Learning

In the year 1814, The Directors of the Company wrote to the Governor General that they intended to spend the amount at their disposal in improving the colleges that already existed (as opposed to setting up new colleges) in Banaras, “to confer marks of distinction on natives, and to inspire their younger civil servants with a desire to study the Sanskrit language.”

“We are informed” they wrote “that are in the Sanskrit language many excellent systems of Ethics with codes of laws and compendiums of the duties to every class of the people, the study of which, might be useful to those natives who may be destined for the judicial department of Government. There are also many tracts of merit, we are told, on the virtues of drugs and plants, and on the application of them in medicine, the knowledge of which might prove desirable to European practitioners; and there are treatises on astronomy, mathematics, including geometry and algebra, which, though they may not add new lights to European science, might be made to form links of communication between the natives and the, gentlemen in our service, who are attached to the observatory and to the department of Engineers, and by such intercourse the natives might gradually be led to adopt the modern improvements in these and other sciences.”

Despite these early pronouncements, the first substantial step was not taken until 1823, when a ‘Committee of Public Instruction’ was appointed, all government supported educational institutions at the time placed under its authority, and it was charged with the disposal of a lakh of rupees per year. The thrust of the Committee continued to be towards supporting (the existing centres of) Oriental higher learning. Another evidence of its support for higher learning was its substantial encouragement for the publication of Oriental books, mainly in Arabic, Persian and Sanskrit.

4.2 Setting Up of English Classes/Departments

Another important measure taken by the Committee in this period was the establishment of English classes in all the main colleges, in the years 1828-30. This step was immensely successful as was indicated by the increase in enrolment in Benares College in one year from 163 to about 270. It is also worth noting here that close to 90% of the students in Benares College at this time were Brahmins and most others belonged to other upper castes. (Thomas, 1891). Interestingly, among all the institutions that were run by the government during this time, the most successful was considered to be the Hindu College – which was the only one in which European literature and science were ‘the staple of instruction’ and which derived it students mainly from the upper classes. Another relevant fact is that while the Oriental printing press was finding it hard to dispose its books, the School-book Society which had been set up by a committee of ‘English Hindus and Muhammadans’ to provide English textbooks, was doing extremely well and bringing in a profit.

4.3 Decisive Shift towards European Education

The Committee had been regularly overdrawing its funds; and in 1833, the funds at its disposal were increased by an Act of British Parliament from £10,000 to £100,000 a year. The question of how the additional amount was to be utilized became a cause of debate in the 10-membered committee. While one side, 5 members were in favour of continuing to spend bulk of the money in improving and expanding oriental education; the other side argued that no money should be spent any more on Oriental learning. It was amidst this debate that Macaulay arrived in India in 1834 and as a Legislative Member of the Supreme Council wrote the famous minute on 2nd of February 1835. His recommendations were endorsed by the Governor-General at the time: Lord William Bentinck, who issued a proclamation on the 7th of March, which gave a decisive hand to the spread of European education in India, through the medium of English language.

Some of the main elements of the proclamation were (1) that the chief aim of the educational policy should be to promote a knowledge of European literature and science: (2) that henceforth no more stipends should be conferred, they serving to encourage obsolete studies (3) that the printing of oriental books should at once cease (4) that the fund thus freed should be employed in promoting European studies through the medium of the English language, and (5) that the Committee should at once submit to Government a scheme for effecting this purpose.

4.4 English Higher Education

The existing oriental colleges continued to receive support; however, what followed was a significant increase in the number of English colleges and students receiving instruction in that medium. In 1835-6, for example, there were 23 institutions under Government containing 3390 students, of whom 1818 were studying English, 218 Arabic and 473 Sanskrit. In 1838 the institutions numbered 38; the scholars over 6,000 of which fewer than in 1835 were studying Arabic and Sanskrit, the rest were studying in English. In 1842-3, 51 schools and colleges contained 8203 scholars, consisting of 5132 studying English, 1819 Hindi, 1504 Urdu, 2718 Bengali, and 288 other vernaculars, 420 Sanskrit, 572 Arabic, and 706 Persian

Thomas (1891) also notes the change in the student-body of the colleges, following Benedict’s proclamation, “The colleges which under the stipendiary system had been regarded by all classes as charitable institutions and were filled with the children of indigent persons [though, of upper castes owning to its focus on Sanskrit] were soon crowded with numbers of the upper and middle classes, prepared to pay, instead of being paid, for an English education.”

Another important point to note here is that new stipends had been cancelled; only competitive scholarships were available – and that too, only to about one-fourth of the total students. This implied that most of the students in these colleges had to pay for what was an expensive education (due in part, to the custom of employing English professors in most departments other than Oriental studies).

- Third Phase: 1854 – End of 19th Century

The East India Company’s charter came up for renewal again in 1853. Among the important issues that came up for discussion (such as the setting up of Indian Universities), was also the issue of elementary education – which had largely remained neglected till then. As Thomas (1891) says,

“There were…indications that the higher classes were by this time not without the power to help themselves, and it was felt that education ought now to begin to ‘filter down’ to a lower stratum.”

The (Wood’s) Despatch of 1854 recommended special attention of The Government of India to the improvement and far wider extension of education, both English and vernacular, and prescribed as the means for the attainment of these objects (1) the constitution of a separate department of the administration for education ; (2) the institution of Universities at the presidency towns; (3) the establishment of institutions for training teachers for all classes of schools; (4) the maintenance of the existing Government colleges and high schools and the increase of their number where necessary; (5) the establishment of new middle schools; (6) increased attention to vernacular schools, indigenous schools for elementary education; and (7) the introduction of a system of grants-in-aid.

A noteworthy point here is that it was almost unanimously agreed that the elementary education should be provided in vernacular medium. Furthermore, two types of middle school seem to have sprung up – the first type were attached to high schools and were generally attended by students who could, or wished to, continue their education after middle school; and the second type were independent middle school, generally attended by those who did not expect to attend high school. The medium of instruction in high schools varied regionally.

5.1 Lack of Progress in Elementary Education

Though the official dispatches and recommendations of the period show a re-focussing of efforts towards Elementary Education, the situation on the ground does not seem to have improved significantly. One possible cause is hinted at in the second despatch on education (1859) which, reviewing the progress made under the earlier despatch, notes that “[T]he native community have failed to co-operate with government in promoting elementary vernacular education. The efforts of educational officers to obtain the necessary local support for the establishment of vernacular schools under the grant-in-aid system are…likely to create a prejudice against education, to render the Government unpopular, and even to compromise its dignity. The soliciting of contributions from the people is declared inexpedient and strong doubts are expressed as to the suitableness of the grant-in-aid system as hitherto in force for the supply of vernacular education to the masses of the population.”

Thus while the grant-in-aid system appears to have worked reasonably well for the other types of education, the lack of local support (among the higher classes?) for elementary education in vernacular medium may have limited its growth. Some of the efforts of the government to invest in primary education seems to also have met the resistance of the small but increasingly vocal professional class who were benefitting from the higher education; as was the case, for example when Sir George Campbell declared in the mid-1870s that one of the main aims of his administration was to encourage primary education, in Bengal (ibid, p. 138). The arguments against such attempts often rested on the ‘filtering down theory’.

5.2 Higher Education

The setting up of the Universities in the year 1857, on the other hand, led to the opening of newer venues for the small and increasingly elite professional classes. “The great aim of the young [mostly upper caste and class] Hindu is to obtain a place in a University examination list” says Thomas (1891), “this being practically the sole public test of proficiency in liberal studies. His ultimate destination is for the most part either the public service or the bar. Out of the 3311 students who obtained degrees between 1871 and 1882, 1244 had in 1882 entered public service, 684 the legal, 225 the medical, and 53 the civic engineering profession.” It was not surprising, given the students that it attracted, that the universities were earning profits in some years just be means of the fees charged to the students.

In 1882 a committee was set up to enquire into the “existing state of public instruction, and to suggest means for furthering the system on a popular basis.” One of the arguments against the education department was that “high education was being stimulated beyond the requirements of the country.” However, the privileged position of the higher education remained more or less unchanged till the end of the century.

- Conclusion

We began the essay by noting two apparent anomalies in the Indian higher education: (a) the disproportionately low participation of the marginalized sections, and (b) the use of English as the preferred medium of instruction in institutions of higher learning, despite the fact that even today no more than 10% of our students study in English medium schools and perhaps no more than 1-2% of the population can use English effectively as a second language. We then raised the issue of whether the roots of these anomalies can be traced to the early years of 18th and 19th century, when the blue-print of the colonial education was being negotiated among the various stakeholders, and whether the social-structure extant at the time had a role to play in this.

Thereafter, in section two, we noted some of the essential features of the native education system as was found and reported by the earliest English researchers – highlighting the dominance of the upper castes in elementary education and the monopolization of the Hindu higher education by the priestly (Brahmin) class. In section three, we described some key features of the first phase of the European education in India, starting in the 18th century and extending till 1814 – we noted, for instance, the early efforts of the missionaries and their focus on providing vernacular education to student, who came mainly from the lower classes; and the initial attempts by some private groups and individuals, as well as Company officials, to support English education for the upper classes.

Then, in section four, we discussed the second phase (1814-54): the Company’s initial support for Oriental learning, which mainly benefitted those classes already conversant with Sanskrit and Arabic; the setting up of English classes in all major colleges; the decisive shift towards European education in English, in 1835; and the growth of English higher education thereafter. Finally, in section five, we described the last phase extending from 1854 to the end of the 19th century and underscored the important changes brought by the 1854 dispatch – including the recommendations for setting up universities and the spread of elementary education in the vernacular medium for the ‘masses’. We also noted how the success of the efforts to spread elementary education was very limited.

It must be noted here that there still exist substantial gaps in our understanding of the Indian education system in the centuries discussed; and there could be, admittedly, more than one way of inter preting the chain of events presented in this essay. However, the following conclusions could perhaps be tentatively but reasonably put forth.

There seems to be little doubt that the upper castes dominated the native education system in the 18th/19th centuries. And though there is evidence that the lower castes formed a substantial portion of the student population (more than 50%) at the elementary level; the higher education, was for and by, the upper castes (chiefly the Brahmins). On account of various reasons (such as, very limited support from the English government, and an entrenched caste system which viewed the missionaries as worse than outcastes) the efforts of the missionaries was largely (though not wholly) limited to basic education in the initial years. And since their primary motive was conversion and not necessarily ‘preparing people for the office’ they focussed their efforts in providing vernacular education and translating religious texts in vernacular languages.

As the spiritual and educational leaders of the Hindu community, the Brahmins seem to have come in more frequent contact with the English administrators, as compared to many other castes and classes. Whatever may have been the reasons, there is little doubt, however, that the major focus of all initial English efforts towards improvement of Indian education went towards improving ‘higher’ education for the higher classes (as opposed to elementary and middle education for the masses).

When the Company undertook to ‘officially’ support Indian education, they encouraged Oriental learning – which primarily benefitted the same class which were already the educational elites and had the ‘cultural, social and symbolic capital’ (if not, or along with, the economic capital) to make use of this education. With the Tols virtually out of access for most other communities, it should not come as a surprise that the Sanskrit college in Benares was overwhelmingly dominated (90%) by the Brahmins in the 1820s.

Gradually, English classes were introduced in the Oriental colleges. (It is notable that this was done at the level of higher education; and to some extent in the high schools). However, as these colleges were filled primarily with students from upper classes, this gave the community a relatively convenient ‘bridge’ to English education. The shift to European education in 1830s brought in a new set of students of the ‘upper class’ (as opposed to the upper caste-but-relatively- poorer students of the Oriental colleges) who could afford to pay their way through college (the stipends had been removed and competitive scholarships were difficult to be won for students of the marginalized sections as they could ill afford home support). Thus, though it may not have been so intentioned (and there are some evidences of the English administration actively working to remove the caste barrier in higher education), this change further helped in strengthening the position of the upper classes in higher education.

Thus, by the time that a refocusing of efforts towards elementary education in vernacular languages was recommended (1854 dispatch) the influential and vocal group of the emerging ‘professional class’ (mostly members of the upper castes) were in a position to oppose such a move on the grounds of the filtration theory – a belief in which, as Thomas (1891) remarks, was perhaps one of the most obvious mistakes of the English administration: “The intensely sacerdotal spirit of the chief Indian caste, the one which benefits most largely English education, is not dead. The rules of caste are as rigid as ever. The exclusiveness which has reigned for three thousand years is as rampant as before. Of anything like public feeling and mutual confidence and help there is no hope for many a year. It is not conceivable that knowledge should under these circumstances filter down. There is no evidence that it has filtered down. Elementary education has no tendency to advance spontaneously, and it has to be carefully protected even front the bodies who administer it. The necessity of first creating an educated class, [it is said], is recognized by the native public opinion. Every statesman who has been suspected of intending to divert any sums from high to elementary teaching has evoked a storm of unpopularity. The case of Sir George Campbell is quoted, whose services to primary education in Bengal we have commemorated. Are these facts in favour of the ‘filtering-down’ theory? The newspapers, it is well known, are in the hands of the class which fills the high schools and colleges. Does their vituperation of Sir George Campbell testify to a strong desire to benefit the poorer classes, or to benefit anyone but themselves?”

While it may not be accurate to draw any firm conclusions from this essay, about the extent to which the policies and practices of the 18th and 19th century may have affected the Indian education system post-independence (and perhaps, continues to affect it even now) – especially as regards two issues mentioned above – it does perhaps hint strongly at a possible relationship between them.

The focus on higher education – which continues to cater to a very small group of well educated, mostly upper class, urban, elites – has been consistently high since independence, whereas the Government elementary education has remained (with the exception of the last 10-12 years) largely neglected. Could this be because the higher classes of today have no use of the Government elementary education? Is part of the reason why English continues to be the predominant medium of instruction in higher education that, as Velaskar (2005) argues, it is part of “the mechanisms through which educational stratification serves the dominant and influential caste, class and political interests and subverts the interests of the oppressed?” No simple answers can perhaps be found, but further exploration of the history of Indian education can provide us with interesting and valuable insights.

- References and Comments

- It is perhaps in recognizing of this that UGC recommends that “authorities would initiate measures, depending upon the need pattern of newly admitted SC, ST, OBC and minority students, to organise remedial or bridge courses in language, communication, subject competency etc.” (UGC Report on 11th FYP, 2011) However, the extent to which this recommendation had been adhered to, and the quality and effectiveness of such remedial courses, remains largely unknown.

- See for instance, Velaskar P. (2005) Educational Stratification Dominant Ideology and the Reproduction of Disadvantage in India. Understanding Indian society: the non-Brahmanic perspective. Edited by S.M. Dahiwale. Jaipur : Rawat Publications

- Acharya, P. (1978) Indigenous Vernacular Education in Pre-British Era: Traditions and Problems. Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 13, No. 48 (Dec. 2, 1978), pp. 1981+1983-1988

- Kingdon G G (2007) The Progress of School Education in India. Oxford Review of Economic Policy. Volume 23, Number 2, 2007, pp 168-195

- Bourdieu, P. (1986) The Forms of Capital. Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education (1986), Westport, CT: Greenwood, pp 241-58

- Mahmood, S. (1895) A History of English Education in India: 1781 to 1893. Published by: The Honorary Secretary of the MAO College, Aligarh.

- Thomas, F.W. (1891) The History And Prospects Of British Education In India. Deighton Bell And Co., Cambridge.

- Viswanathan G (1988) The Politics of British Educational and Cultural Policy in India, 1813-1854. Social Text, No 19/20 (Autumn, 1988), pp 85-104

4 thoughts on “History of Indian Education”

Hi,

I’m Guru Ramkoushik from Verzeo.in

I have seen your blog about

” history-of-Indian-education ”

http://theeducationist.info/history-of-indian-education/

Which is so impressive, and as contextually relevant to our blog: https://verzeo.in/blog-edsystem

Thanks for your comment, Guru.

यह अविश्वसनीय नही है कि भारतीय समाज शिक्षा के मामले में समृद्ध था। धर्म,मंदिर,विद्यालय और पढ़ने वाले बच्चे आपस मे जुड़े हुए थे और पक्का उस औपचारिक माहौल में कुछ रचनात्मक करते होंगे। इस विषय पर कुछ और ज्यादा शोध की जरूरत हैं। मैं इसका एक और पहलू भी देखता हूं, इस रिपोर्ट में भी ब्राह्मणों को डोमिनेट दिखाने की कोशिश की गई है जो कि बिना सही संदर्भ के ही बताने की कोशिश की गई है जो कि एक अनुसंधानकर्ता के लिए आदर्श बात नही है। आप ऐसी और कोई जानकारी साझा करना चाहे या विमर्श के लिए संपर्क कर सकते है। धन्यवाद

दिलीप

Dhanyawad Dileepji. Is baat mein shayad hi koi sandeh hai ki samaaj ke kuch wargon ke liyeay, shiksha ke marg awam awsar, doosray wargon ki apeksha mein, behtar they. Ismay brahman, vaishya aur musalmano ke uchha warg shamil the. Magar mai aapki is baat se sahmat hun ki isse iske sandarbh mein dekha jana chahiyey – iske anekon karan they, aur un karonon/sandarbhon kee bhi baat ke jani chahiyay.